Ah, but a man's reach should exceed his grasp,

Or what's a heaven for? —Robert Browning

A little over two months ago, me and my friend found ourselves in an unwelcome but strangely freeing situation… lost in the arcane, anaemic public transport ‘system’ threading Corsica’s unvarnished landscapes.

As you may understand, starting a photography business is a perilous risk, with half of all who try failing in the first couple of years, and despite—or even because of—my glossy online presence, I am not an established name. Work hasn’t come easy, and there’s grit under my nails to show for it.

I have no fixed home. No second income stream tucked neatly into a study or spare room. Instead, I move. I think sideways. This isn’t new for me—I’ve always drifted toward the remote and the unconventional, toward lives lived outside the polite.

That restlessness carried me to Corsica—a place I half-hoped, half-feared would be the making of me. My friend and I signed on to volunteer for a month with an elderly Germanic couple, welcoming us to prepare the garden for the bulk of the growing season.

But it soon became clear that welcoming was too generous a moniker, as the old man’s attitude, despite living in a veritable Eden, was about as backwards as their hygiene principles—quite literally lick-the-plate-clean water austerity and rather cosmetic refrigerators. Which, although we dodged unheated rice and questionable cured meat offerings, struck my friend down with severe food poisoning as well as severe pains and inflammation from gluten she had accidentally been served. This, in combination with many other problems, compelled us to leave… and with that—and after considerable rest in hurriedly booked hotels—a window to a chance photography opportunity opened just a sliver.

For where we had been was as unscalable by anything other than car or impossible humid stretches of hiking over the lush eastern slopes. But where we now based ourselves was in Corte—a central, decaying town over which atmospherically loomed the highest peaks of the country. It was typical of Corsica in the sense that it was a crumbling patchwork that didn’t hide its decay nor its associated lifestyles—a raw authenticity that charmed me. It’s also a hub for intrepid hikers.

There is a well-known and highly challenging hiking trail called the GR 20, which runs west along these mountains west of Corte. I had toyed with the idea of climbing Monte Cinto (the highest peak), camera in tow, but research led me to conclude that height was not synonymous with soul. I have a contrarian streak that nudged me in the direction of the less-climbed Monte Rotondo. I’m an intuitive photographer, and a “little” seven-hour scouting hike along a neighbouring ridge had convinced me: this is the one.

Allow me the indulgence of digging deeper into my way of thinking at the time. For me, this felt like a culmination. In my photographic journey, I had exhausted the classical, technical low-hanging fruit. Composition, colour science, crop, angles, rules, f-number, ISO, hyperfocal distance—these had long become chef-like intuition. I no longer consulted the camera like a learner driver. It was an extension of me, as familiar as the skin on my face. I even interrogated ChatGPT to uncover blind spots I might have missed.

What began to form in my mind was more daring, more authored, more impactful than anything I’d created before. My earlier work—individual landscapes, technical studies, portfolio pieces—was a practice paper. This was the marrow. The meat and bones of my craft. A step change in how I saw, and a refinement of what I wanted the world to see. This mindset wasn’t accidental. It was a deliberate psychic setup, cultivated to courier my mind to that intangible, beautiful place.

But the honest locus of this drive—the silt and mud from which I grew—was desperation and pain. I had to get it. I had to become what I sought, arrogantly, youthfully. I wanted everything. Because most of my life had been a story of just squeaking by; of living out of my parents’ shoe. I’d become obsessed, as I still am, with perfection, with love, with beauty. With tearing myself out of a culture of tailored mediocrity—a quiet death of ambition dressed up in polite resignation. I wanted to punch a hole in the sky.

The quixotism of that quote wasn’t affectation. It was real. There was a flame in my eyes that felt like another being—sharpened by years of caution, billowed by an inner fuck-you to the universe. I would live my dream, even if it cost me everything.

And that is no exaggeration of my psychic state when I stepped out of the motel door at 8 a.m.

It was forecast to be 28°C and cloudless. Perfect, I thought, because the T-shirt that was appropriate down here would also be appropriate for the coolness of the 2600m slopes when traversed at speed. And I would need to move fast. I was carrying a full-frame mirrorless with a 24–70, which is about as much weight as you can get away with. The route was long—too long. The scout hike had tempered my expectations, so I was covering the same mileage with added height. I was taking an unusual and hardly travelled route that would actually skirt the summit on the east side and then loop back just short of connecting to the GR 20.

The issue was, the long winding road up the Restonica Valley I would rather drive than walk—but hiring a car wasn’t happening, nor was catching a bus. My advice if you ever want to tour Corsica is to sort out car hire straight away, as public transport is barely existent—and when it does exist, it exists in a typically French, if-you-know-you-know, laissez-faire fashion. Tourists are a mixed bag in their eyes, especially if you don’t speak French or Corsican. They are, per the stereotype, somewhat proud and old-worldly. CORSICA IS NOT FRANCE. They take time to trust you and don’t speak to please. So my last resort was to run the distance quickly (I’m a near-elite long-distance runner) if a hitch-hike became intimidating. The gunshot holes in the road signs soon reinforced that idea, just shoring up the “we have generation-long vendettas” myth in case visitors like me somehow forgot. So running it was to be—surprisingly not too tiring. I didn’t consider this part of the hike, so the distance in the mountains was about 12 miles. I was okay with it taking all day, as the daylight was long in May. I had enough food and could potentially, I thought, refill my water from high snowmelt if it came to it. The snow I had seen from my scout hike, but it seemed patchy and therefore traversable.

Anyway, there was to be trouble long before thoughts of snowmelt entered the picture, taking the form of not one but two road bridges destroyed by previous floods. No warning, just suddenly tarmac disappearing Looney Tunes style into the void—round a corner too. “Very cool, very Corsican,” I thought, with bemused German cyclists looking on. Well, at least I could go where they couldn’t (with great difficulty, balancing on a log over uninsured camera-doom waters). Thankfully, the second broken bridge I half-expected was smaller.

Note about the weather: Corsica is blessed/cursed with extremes of sun and storms. It can be bone-dry for months, but when it does rain, it pours due to moist air being forced up over the mountains.

The first leg of the ascent took me zigzagging through pine forest, bringing me the first of a few unanticipated perils: processionary pine caterpillars. Thousands of them, forming 10-metre-long trains all over the path. A bit of research revealed this is a sign of climate change, and bad news for the forest.

But this is about photography, and I soon emerged into a rocky region of hardy birch and scrubby, thorny bush at roughly 1600 m. I was getting intimate enough with the cul-de-sac of the mountains to get that “man doesn’t tread here often” feeling, as well as the acute sense of being the exceptionally small, vulnerable bag of organs that I was. It was approaching midday, and the sun was high, with zero shade, as I expected. I had mapped the sun’s path with PhotoPills. Anyway, time to refuel and reapply sunscreen, rather than shoot. I know I usually don’t shoot my best early, and the light was flat, although I was glad to see some plumes of cloud building behind the summit. The landscape and rivers were becoming stark and intriguing, but I wouldn’t settle for a postcard.

It was shortly after passing, on my far left, what appeared to be a kind of mountain bothy near a stream, that the path degraded into mostly the orange dot system I was used to. It became a hard and unsteady climb, with large loose rocks and multiple unclear routes to the next dot. I did think to myself, “This work rate is going to be a challenge”, and my water was already half gone. 1 pm.

The mountains can do strange things to people. Maybe what I was experiencing now was what Edmund Burke called the sublime, or maybe it was mild hypoxia. The emptiness, the windless solitudes, the l'appel du vide of looking back down the valley, brought the palimpsest of my emotional journey to the fore. A deep awareness of my vulnerability as an organism, the parallels between my climb and my struggles, my naïve earnestness to succeed, formed a psychological cascade; you might call it a solipsist’s anxiety, but there was a thrill to it too.

So too did the mountain feel more like an organism. Perhaps it was a projection of a protesting stomach, but the pulmonary grooves of green blooming from grey scree enchanted me. So did the light: it presented a little fall-off to catch highlights and enunciate the shadows. It was here amid ridges and the last remaining pines that I began to capture.

As an aside, you may, as a photographer, wonder: why these mountains? Although beautiful, it is hardly a must-go destination for photography. It sits in a middle ground—you don’t see this in the Peak District, but it’s not overtly cinematic or striking as compared to the Italian Dolomites or Iceland, for instance.

The prosaic explanation is that I can’t afford to travel just for photography. But there is a romantic answer too. My philosophy is: you can only do half the honour with the subject. The rest—perhaps the majority—is how it is seen, what it speaks, the feelings evoked, the honouring of time and place, the immaterial in the material. These are tied to your vision and authorship as a photographer. The world is not, as the quantum revelations suggest, a fixed material object—separated, untangled, and independent from the capturer. You get a blow to the head from a rock, see how your world spins. So I can look at technically perfect landscapes of Iceland or Mount Fuji, and I admire them—the close-enough-to-real, slightly Netflix-escapism contrast and colours, the pitch-perfect f/8–f/16 sharpness, the 16 mm wide with no space left unconsidered or untouched. Great. Stunning. But not for me.

I want to take the photo when I sense something I don’t yet understand, and bring it out, so that whatever it is, a strand of hair on the hotel floor, the ash in a cigarette tray, shines just so—that boundless enigma of being.

So I started parsing my subjects. But subjects are not always things. Sometimes the entire palette of the scene is the subject, with no distinct form on which the eye rests. I passed more cliché outcrops of dead trees and crooked rock formations than I care to name. I wasn’t looking for them. I was looking for Corsica in a grain of sand.

Do you believe in God? Do you see a cruel, unforgiving ball of soil beneath you, of which you are not a part? Or do you see the sun as your doing? Or you as the Earth’s doing? Jordan Peterson, as much as I disagree with him, has a definition of God as that which is the highest undergirding value man and woman have—it is the hidden assumption. Why did you get up today? Work, perhaps, the surface reply. But why work? Your wife? Your kids? Your survival? But why survive? Maybe it’s not thought out—it’s just impulse. Yes… but what is that impulse? That energy that says yes. Yes yes yes! to everything already.

I’m not religious. I’m not with any answer to such a question. But it’s this space between question and answer, like a Hintergedanken, that, in the exquisite moment, is me pressing the button when I do—it is life seeing life without glasses.

And yet on this day of all days, I don’t feel it. I line up shots—many good compositions, solid geometries, weird erosions, burnt lifeless plains… all too plain. All too honest, normal and seen before, done before. It groans with the weight of me trying. It strains with the adjustment of angles, the ND adjustments, the bracketing and the focus stacking. It’s burdened with my desire. My wish for it to be more than it can be. I want to say “Forgive me, mountain, for I have sinned,” but I do what I always do—I stop when it no longer excites me. Sin is my lyre, mountain.

Sometimes something leaps out at me, like the outcrop below, and I scramble to compose, and satisfaction seems commensurate with my task. But then I look at it again and again. You see… it lacks something. You may even be ‘technically’ able to pinpoint exactly what those weaknesses are: depth, crop, straight-on angle, lighting, lacking middle-ground interest. Yes, maybe… but then I remember my authorship, my eye—that the subject is innocently what it is. This is how it appears now. I cannot bend the subject to my will, but I can change how the subject is seen—how the act of seeing is part of what the image is. How presentation evokes feeling before cognition even has a chance to catch up.

Of course, I never thought of all this, verbatim, at the time. It’s a story told after the fact—nobody maps their intuitions in real time.

3 pm. The peaks are peeking from behind a crest a small lake is nestled in like a tame caldera. I’m shocked at the lack of progress. This isn’t even two miles into the 12-mile portion of the mountain. I knew the ascent would be the slowest, but I’m becoming nervous. So I settle with not straying from the path for pictures—for now, at least. Although not straying from the path was taking most of my mental load, the closer I get to the lake, the more the peaks seem to rise in relief.

The snowmelt was also becoming a problem. Parts of the path go both through bog and whippy, hard-as-nails bushes. My legs scratched like the victim of a cat’s angst.

…then comes the impassable mass of snow. Much more than I expected. I see bootprints, so I assume it is traversable, which proves true for about four seconds, as my boot lunges through two feet of icy slush sandwiched between two sandpaper boulders. My foot dips into a stream of water running underneath.

I don’t know what compelled me to continue, but I did. Maybe I was high on the luck of avoiding spraining my ankle earlier, or the expectation that the snow might be harder and more grippy further up.

It was not.

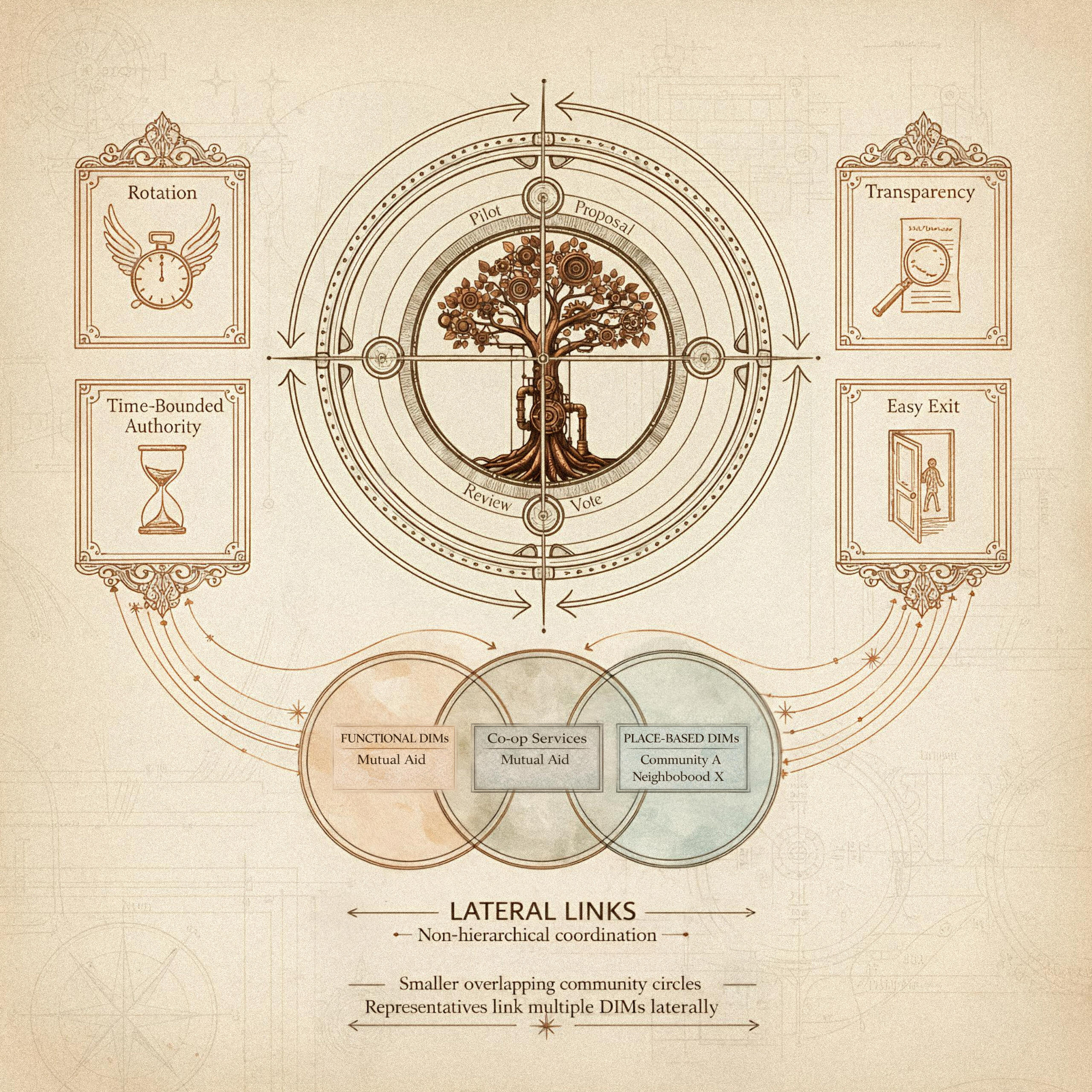

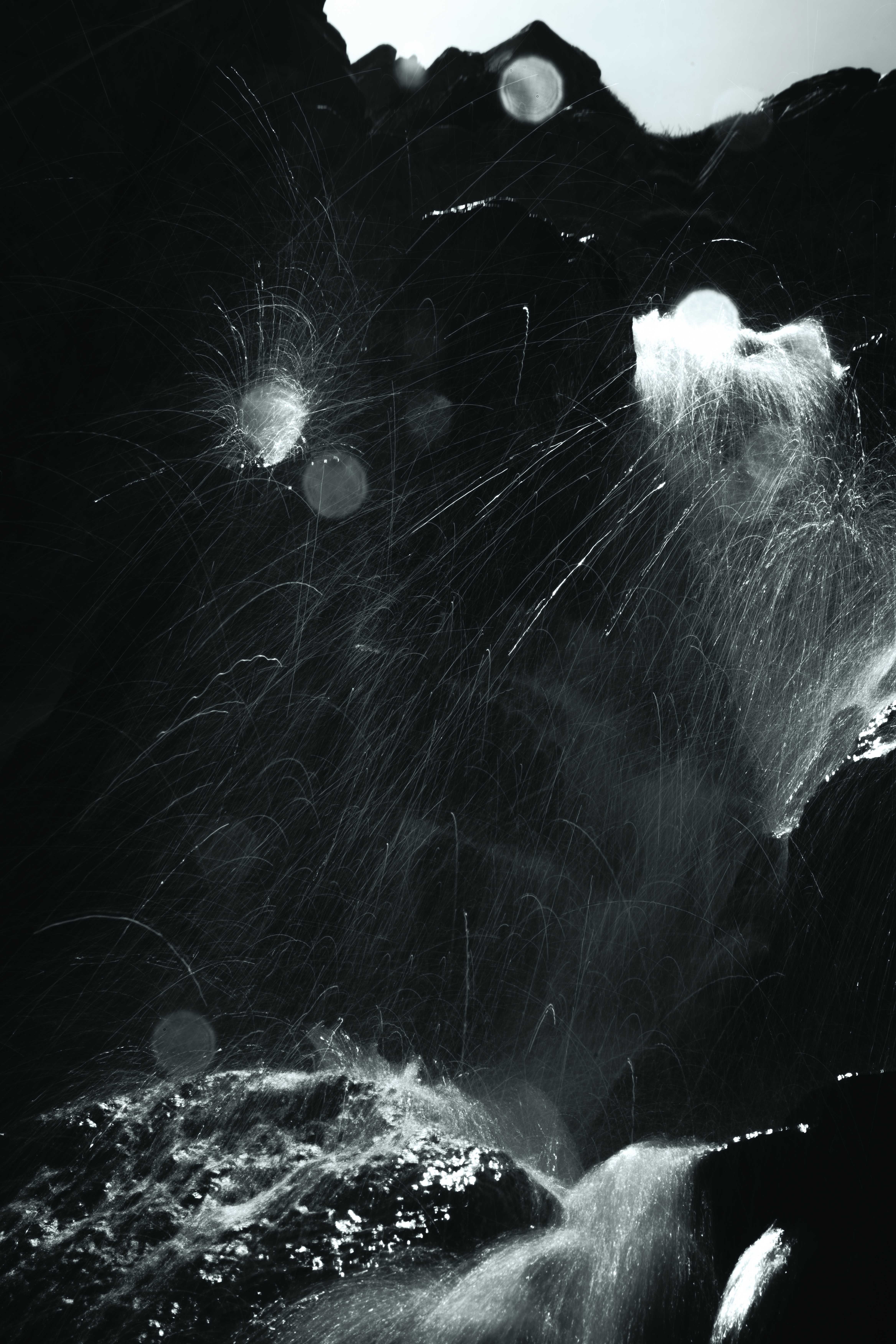

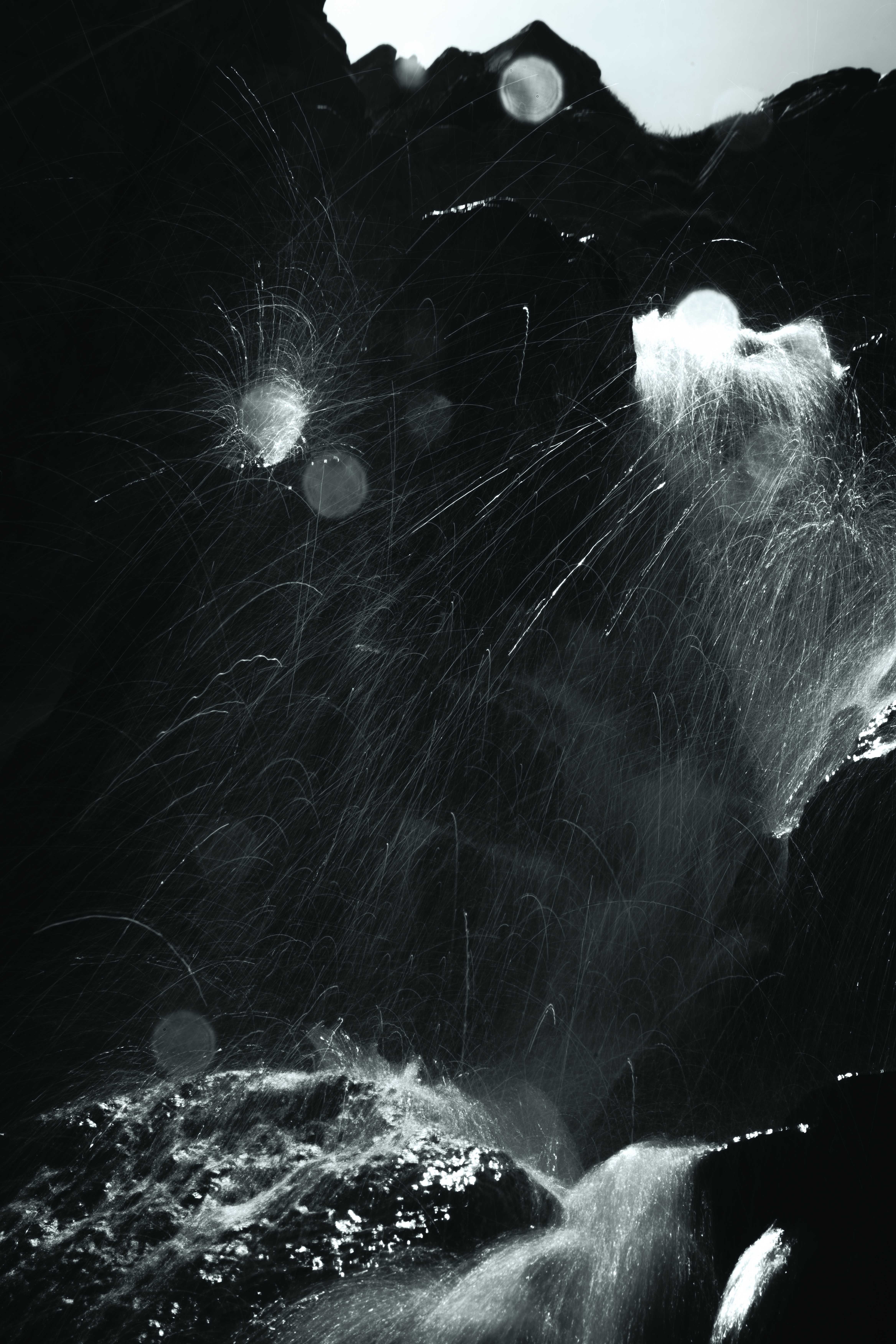

But somehow I arrived at the lake shore. It was, disenchantingly, rather nondescript. I consoled myself that this was one of three or four lakes on the route. One of three or four… but I was out of water. The water looked crystal clear, and I doubted there would be animals that could pollute it—2300 m or so—but the last 300 looked like 3000 from where I stood. In any case, I wanted to be closer to the source of the snowmelt just to be safe. By chance, I spotted a waterfall along the route I was having increasing trouble finding, and then I lost it… completely. All I could see were walls of snow, and it dawned that my ascent was over. Still, I needed that water, so I half slipped, half crawled to the base of a near-vertical cliff face, throwing icy spray sparkling in the sun. The relief of finding a reliable source was palpable. Without particular expectation, I shot a few long exposures—as you can see below. Two of these later became overlays, which I would double-expose over the final landscapes.

Coming down, in the literal sense, was uneventful, save another near-sprain and a tricky deviation into a cow-trodden birch thicket, the light now positioned perfectly for my descent on… the other side of the mountain ridge. Anyway, with the light raking the side of an impressive northern protrusion, with what appeared as an animal’s desire path curving leftwards through stunted pine—I composed at eye level, 70 mm, f/8, deliberately clipping the peak. This one came more with the intimation of asking to be seen, rather than searching with the eye.

I arrived at our hotel at 9 pm, bruised, exhausted, sunburnt from the waist down, and sticky with sweat and grime.

Photographs can never be what one imagines; their imperfection is what makes them stubbornly alive. Still, I had nursed a fantasy that the mountain might open like a temple, hand me its secrets, bless me with revelation. Instead, it gave me bruises, false starts, and silence.

And perhaps that’s the point. I am not the master, not the pilgrim-priest, but simply an organism clambering through light and stone. What remains, after the hunger and the ache, is the part of me I keep trying to outgrow but never do.

Corsica wears its years openly—worn, indifferent, baked by sun, eroded by wind and rain. Many a weathered face on this island. But me… I’m still that starry-eyed boy.